The Importance Of Guitar Repertoire

The Importance Of Guitar Repertoire

“Guitar Repertoire” is the music you know how to play, not the music you’re learning, or struggling with.

If your first response is to say “I struggle with everything”, even as a joke, you might want to take another look at what you’re practicing. The “how” of practice is crucial, and one of the places many students go astray. But the “what” really matters too (hint: it includes your guitar repertoire).

A well-rounded practice routine should include technical work, learning and improving new material, and executing something fluid. The last part is what many people are missing.

When you practice, are you always at the edge of your ability?

If so, you should add in material that’s easier. Learn a song with two chords and practice staying in the pocket. Play a simple, satisfying melody. Just because something is straightforward doesn’t mean it’s not worth revisiting. Ask yourself how you might improve your performance. Often, this takes you into more musical territory, thinking about the things that make one person’s playing stand out from another.

Students will often ask how it is that a skilled player can make an easy part sound so much better. After all, you just need to hit the right notes at the right time, don’t you?

You likely already know that the above sentence isn’t true. Fluid players make the music sound better because they’re tuned in to musical elements like tone, dynamics, and feel. Practicing those things is not as clear-cut as working on technique, because they aren’t absolute. When it comes to technique, you either hit the note or you didn’t. But when it comes to musicality, there’s no standard other than that it “feels” right, and it’s impossible to hear if you don’t know what you’re listening for.

It’s worth remembering that even the most iconic players have a guitar repertoire of music that’s theirs.

Performing artists have songs they’ve played again and again, to the point they know the music inside and out. When you listen to your favorite recordings, you are often listening to musicians that have focused on and polished a relatively small amount of material. The average bar band plays more songs in a night than your average pro on the big stage! The players on your favorite albums probably worked that set of songs exclusively for weeks at least, unless they were hired session musicians. And session players play new music ALL the time, so their ability to learn and master quickly is highly developed. But a band is going to be well-rehearsed when you hear them on a record or on stage.

What does this mean for your practice routine?

It means that in order to feel any real sense of accomplishment, you need to build a set of music you can really play. If that means baby steps, and music that’s not necessarily your ultimate goal, that doesn’t matter. When your middle schooler goes to band rehearsal, they play simpler parts than they might learn for a solo. But those simpler parts let them concentrate on playing together, which is a very different experience than practicing in front of your computer.

You don’t need to have a group to practice with, although it’s by far the best way to develop a guitar repertoire. Lacking the pressure of an upcoming performance, many people never even play a complete song from beginning to end!

You can prepare for an imaginary performance, or serenade your toddler or your dog. Work on performing a whole song on camera, with the knowledge that no one ever has to see it. Choose songs that are attainable and fun. You might need a teacher’s help for this, but if you make a wish list of 10 songs you’d like to learn you should be able to figure out which is most accessible to you.

Pick out two or three “campfire” songs you could play with a simple strum. You might be surprised how many people never do this. No amount of time spent on scales, speed drills, and spider exercises will prepare you to perform a three-chord song with strong rhythm and a good sound.

“I’m going to walk before they make me run.” – Keith Richards

So even if your goal is to run like the wind, make sure you can manage a leisurely stroll.

Interested in more guitar lessons and courses? Check out JamPlay.com. JamPlay has over 450 guitar courses from 120+ instructors, and online guitar lessons tailored to every skill level, music genre, and playing style. Click here to learn more.

Dave Isaacs has established himself as a guitar teacher extraordinaire, having built a strong set of educational curriculums for beginner, intermediate, and advanced guitar players alike. Dave shares his expertise largely through video platforms, but also through his thoughtful writing. You can take guitar lessons from Dave Isaacs via his comprehensive video guitar courses on JamPlay.com.

Share this

Become a JamPlay member for unlimited access to 7000+ guitar lessons and 120+ artists and instructors. View membership plans ›

Related Posts

Why Practice Scales?

Why Practice Scales?

Scale work is a basic part of many guitarists’ practice routine.

Teachers routinely assign scales and talk about the importance of “the 5 positions” or “CAGED theory”. This is useful information, to be sure, but many students are still left confused. Why exactly do we practice scales, and how do you use that knowledge to actually learn to solo?

1. Precision and accuracy

The ability to get your fingers to land where you want them to is pretty fundamental to good guitar playing. You can practice facility and accuracy with anything, provided you slow it down enough to stay in control of your fingers. But scales are a good way to develop technical skills because the movements are going to show up in the music you play. The same can’t be said of many pure finger exercises like “spider” patterns. These have their place, but for the most part these exercises are purely mechanical and have no real musical application outside of occasional sonic weirdness. (Which does have its place…check out Jimmy Page’s dissonant signature riff in the Firm’s “Radioactive” from 1985).

2. Fretboard mapping

Guitar is not a linear instrument like a piano. The notes on a single string are, in that moving up the neck one fret at a time walks through the chromatic scale just as striking every key on a keyboard would. While we do often play linear moves along the same string, a scale fingering is going to cross strings. Now instead of moving in a straight line, we’re navigating a matrix.

This means there are multiple paths to the same place.

It’s possible to work through all the different combinations in an organized way, but most people don’t. To be fair, you might not need to. Lots of iconic players used the same patterns again and again, and it didn’t bother them or us. So it’s not necessarily true that you NEED to know every possible variation. The more options you have, the better, but not if it only creates confusion.

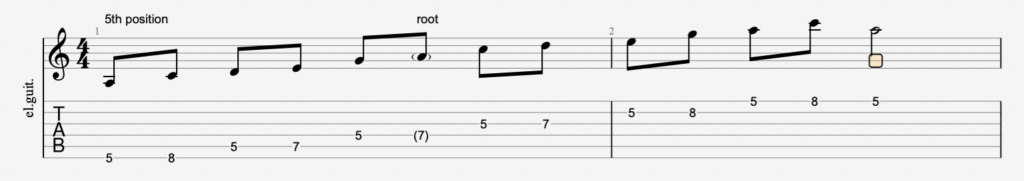

With that said, once you’ve learned one form or pattern, that should help you learn the next one. If you are learning the “5 positions/CAGED” model, it will really help clarify things if you look at each shape as a variation on the last. For example, let’s say you’re starting with a familiar A minor pentatonic in the 5th position:

If we’re following the “5 positions model”, the next form would be played in the 7th position:

Rather than learning these as two unrelated things, look for the places the patterns overlap.

Notice the shared root note on the D string (in this case, at the seventh fret). Use this as an anchor or landmark, the same way you might use a 6th string bass note to identify a barre chord.

Try playing simple melodic fragments in both positions, hitting the same notes with different fingering:

Don’t let this be dry, uninteresting work! Playing short scale fragments in different places is absolutely key to developing your fretboard knowledge and mental flexibility. Fluid players have absorbed the fingerings to a point where they think in ideas and phrases and the fingers know how to articulate them. But if all you do is run scales up and down the entire shape, that’s all your hands will know how to do.

Remember that “licks” are just recognizable combinations of notes from a scale (or combined scales).

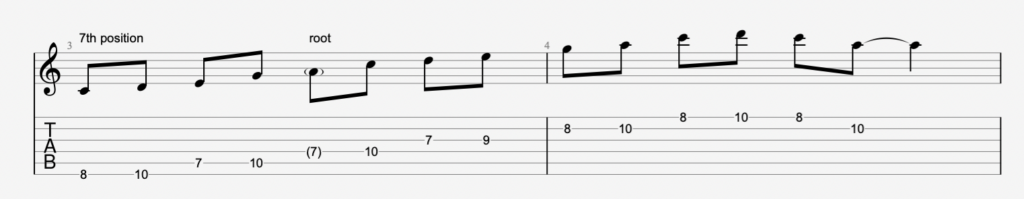

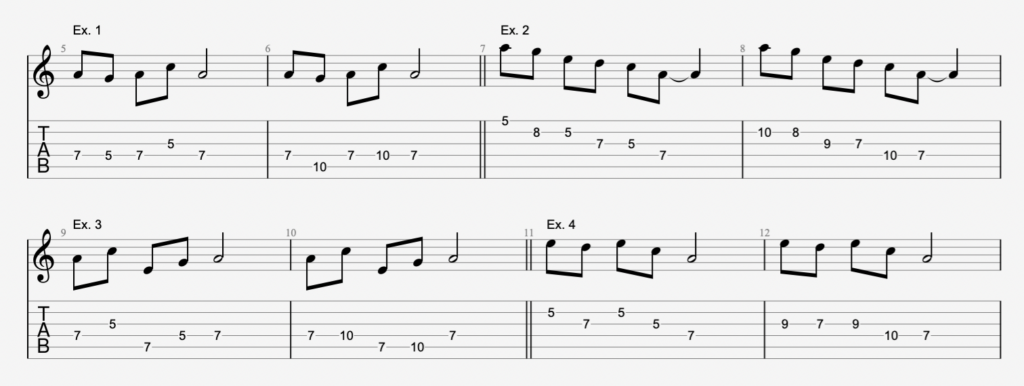

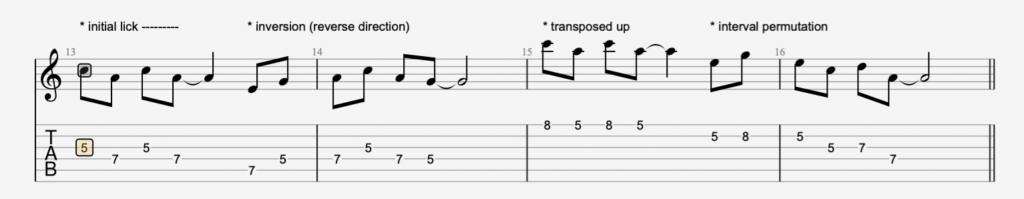

So you need to learn not just patterns but permutations. For example, here are a series of variations on a 4-note lick. They’re all derived from the same minor pentatonic form, and are related either through pitch, melodic shape, or rhythm. These relationships are what make them sound coherent as a series of unfolding variations. The consistent rhythm helps reinforce the sense of call and response, a very natural way of organizing phrases.

3. Ear training

If we’ve established that a scale pattern is a map, it would make sense for us to identify locations along the path. We can do this by note name, and there’s value to that information. But improvising musicians are not thinking of note names. Rather, most are listening to patterns and relative relationships.

An “A” root of a minor pentatonic scale sounds completely different when that same A is the seventh of a Bb major scale.

We learn how to use the scales by identifying the individual notes not by name but by their quality and position in the sequence. This is a long process to master for most people, but it starts with listening. Label the notes as you play patterns: for a minor pentatonic, it’s root, minor 3rd, 4th, 5th, minor 7th. These are recognizable sounds, and the more closely you listen the more commonality you will begin to hear.

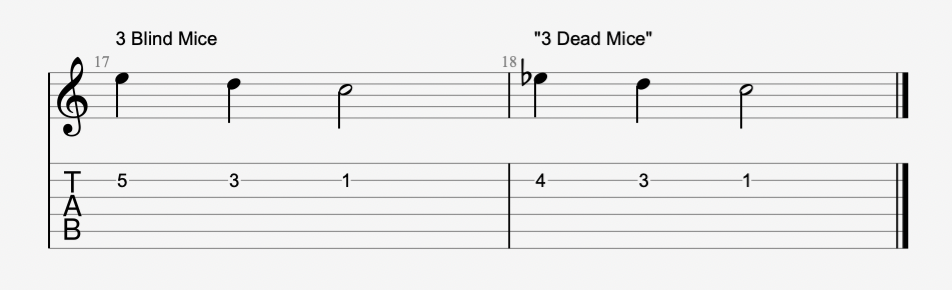

Most people’s ears are more sophisticated than they realize, once they know what to listen for. Rather than thinking of all of this as a series of mathematical formulas, think instead about colors, flavors, and feeling. Listen for tension and release, clash and blend, drama and calm. If you don’t “hear” it, keep listening. I like to use this example when teaching young students the difference between major and minor:

It usually gets a laugh, and it makes the point. You don’t have to be musically educated to listen for the difference between sounds. In fact, the way to get educated is to just start listening.

One great trick is to play scales against a drone (one consistent note).

Here is a useful YouTube playlist you can use for this purpose:

https://youtube.com/playlist?list=OLAK5uy_kQHsbDd1hllwmhD_0MZuhvuIu_P5zLCTI

Playing the scale against the drone lets you hear the differing degrees of tension between different notes of the scale. Try identifying small fragments according to the order of notes in the sequence:

- Root through the 3rd and back (1 2 3 2 1)

- Root through the fifth and back ( 1 2 3 4 5 4 3 2 1)

- Major triad (1 3 5 3 1)

- One octave scale (1 through 8)

If you try this exercise with every scale you learn, you will quickly have a better understanding of the musical elements each contains. The fingering pattern is only the first step of an ongoing process of mental mapping, ear training, and conscious exploration.

Remember, scales are not “boring but necessary”.

Learning scales is one way to get to know the fretboard while developing your facility and your ear. But it’s crucial for that practice to include music, not just locations on a fretboard.

Interested in more guitar lessons and courses? Check out JamPlay.com. JamPlay has over 450 guitar courses from 120+ instructors, and online guitar lessons tailored to every skill level, music genre, and playing style. Click here to learn more.

Dave Isaacs has established himself as a guitar teacher extraordinaire, having built a strong set of educational curriculums for beginner, intermediate, and advanced guitar players alike. Dave shares his expertise largely through video platforms, but also through his thoughtful writing. You can take guitar lessons from Dave Isaacs via his comprehensive video guitar courses on JamPlay.com.

Share this

Become a JamPlay member for unlimited access to 7000+ guitar lessons and 120+ artists and instructors. View membership plans ›

Related Posts

Organizing Your Guitar Practice Time

Organizing Your Guitar Practice Time

I hear frequently from students that they don’t know what to focus on, or how to organize their guitar practice time.

There’s so much material out there, and so many things to be interested in. How can you possibly find time to do it all? You can’t, of course. If you’re like most people, you carve out time to play guitar wherever your life allows it. So wondering whether you’re spending it productively is only natural. One good way to do this is to divide your guitar practice repertoire into categories:

-

new material you’re learning

-

songs in progress you’re working to improve

-

songs you can comfortably play

One powerful approach is to establish a “practice pipeline”: a method and process to move a song from the first stage to the third. When time is limited, this is a great way to make sure you’re moving things forward. We do this by setting specific goals, depending on where in the process you are.

- Learning new material, the goal is to get to know the notes.

- Polishing material, the goal is to identify and work out the trouble spots.

- Performing material, the goal is to maintain a comfortable flow through the song.

Even if you only had time to work on one song in a given practice session, you can make a measurable improvement in one of the three areas. Learn a new lick, or take a closer look at why you’re finding a particular part so challenging. Put your problem-solving skills to work, or spend fifteen minutes with a jam track. In each case you’re focusing on one of our three primary areas: absorbing, polishing, and flowing.

This approach is even more powerful when you follow a thread through the guitar practice routine. Things like technical exercises and theory can connect to the songs in your pipeline. For example, you might practice a finger pattern in preparation for learning a more complex lick. Or you might analyze the chord structure of a song to help reinforce your ear and memory. It’s easier to remember an unfolding story than a disconnected series of events.

Once you’ve categorized your material, it’s easier to decide where to focus.

Don’t worry about getting to everything if time is limited. The ongoing process is the most important part: returning again and again to your guitar with a specific intention.

Remember also that repetition doesn’t automatically equal improvement. If you work with a teacher or coach, you would expect feedback on your execution and form. So be your own coach. Be aware of more than just whether or not you nailed the note. Often, the issue is not in the landing but in the movement to get there. Never practice technique blindly, whether it’s an exercise or a lick from a song. Your goal is continual improvement, and it wont happen without looking at the “how” as much as the “what”.

If you miss something repeatedly, there’s a reason, and it might not be that it’s beyond your ability.

Even if that reason is limited technique, taking that closer look will reveal how to surpass that limitation.

Performance or flow practice is also hugely important. If you aren’t playing actual music, it’s difficult to really grow. “Actual music” is also not necessarily difficult. If you aren’t having fun at some point doing something simple, you’re leaving out the best part! Besides, there’s more to playing a song well than just nailing the chords. When I was learning to play, I might think a repetitive three-chord song was boring. I didn’t understand then about dynamics, or the concept of shaping a performance. The places your fingers need to land are just the beginning steps. Learn about pocket and groove and tone and energy. Be able to play your parts without staring at your fingers, or locking your whole body in concentration. When you can flow and move as you play, you’ll perform with a lot more confidence. You’ll also enjoy the experience that much more.

Above all, focus on the process.

If you accomplish something small every time you pick up your guitar, you will see progress. Concentrating on a small number of things at a time keeps you focused. Rotating those things keeps you engaged. Doing it again and again intentionally keeps you growing.

Interested in more guitar lessons and courses? Check out JamPlay.com. JamPlay has over 450 guitar courses from 120+ instructors, and online guitar lessons tailored to every skill level, music genre, and playing style. Click here to learn more.

Dave Isaacs has established himself as a guitar teacher extraordinaire, having built a strong set of educational curriculums for beginner, intermediate, and advanced guitar players alike. Dave shares his expertise largely through video platforms, but also through his thoughtful writing. You can take guitar lessons from Dave Isaacs via his comprehensive video guitar courses on JamPlay.com.

Share this

Become a JamPlay member for unlimited access to 7000+ guitar lessons and 120+ artists and instructors. View membership plans ›

Related Posts

3 Tips For the Discouraged Adult Guitarist

3 Tips For the Discouraged Adult Guitarist

Every musician gets discouraged sometimes.

Let’s face it, the path of guitar is frustrating, especially when time is limited. If you don’t see and feel progress, it’s easy to second-guess yourself. You may feel this way especially if you are an adult guitarist.

It’s possible that if you feel stuck, your practice method may need adjusting. Effective practice does allow you to gauge progress when you keep your goals modest and organized. So if you’re not seeing improvement, you may not be paying attention to the right things. Self-awareness and a problem-solving mindset will always pay off in the long run.

But it’s also possible that you’ve lost perspective. After all, most people are trying to fit guitar practice into an already busy and complicated life. When you find yourself wondering if it’s just too difficult to learn to play as an adult, it’s helpful to keep a few realities in mind.

1. You don’t need to know everything.

It’s easy to be overwhelmed by just how much there is to learn. It doesn’t help when the internet guitar world tells you things like, “every guitar player must know their modes” before you’ve learned to play rhythm through a complete song . (You can substitute any number of musical subjects).

Learning something new about music is never a bad thing, and every new piece of data is a potential tool in your toolbox. But there are no absolutes. You can be sure that there are musicians you have admired your entire life that have a very limited skill set. Most of our heroes were not formally educated. With very few exceptions, most work within a single style and with a basic sound. That sound came from somewhere, of course, and they might know that territory deeply. But there is a difference between a player that develops a personal sound and a player that develops the skills of a working freelance musician.

If your interests are broad, there’s nothing wrong with being diverse. But having a musical home base to explore will keep you focused on the skills and knowledge you need to play that style. If that home base is the music that moves you most, there’s always more inspiration to be found.

2. Simple is satisfying.

I learned a very valuable lesson one summer, when I went from an intensive jazz camp to a folk music retreat. I was about to start a masters degree in music, and saw myself as an advanced, sophisticated musician. But jamming with the folkies, I realized that all my musical knowledge still didn’t prepare me to play with people that knew a style intimately. These were very skilled players that left me in the dust with their confidence and authority. My chops and vocabulary were irrelevant without a mature listener’s sense of when NOT to play.

Of course there’s a place for virtuosity, and great skill is satisfying in itself. But strumming a simple groove as well as it can be played is equally rewarding – especially if you can get a room full of people dancing in the process. If your practice is not giving you the skills to do something simple well, you’re not practicing the right skills.

3. Move the needle.

The goal of every single practice session is to finish it knowing something better than you did when you started. In other words, any improvement counts. It might be that you were just a little bit more familiar with something than you were the day before. It might be that you committed a single lick to memory. Progress isn’t measured in leaps and bounds, but in tiny steps. It’s important to enjoy the process, and for your practicing to be an ongoing series of small, measurable goals. If you can’t find something that lets you take a small win, look more closely.

Above all, maintain your perspective.

If you’re struggling to the point that it’s frustrating and not enjoyable, shift gears. Feeding the love is the most important part, and remember, there’s a growth opportunity in everything.

Interested in more guitar lessons and courses? Check out JamPlay.com. JamPlay has over 450 guitar courses from 120+ instructors, and online guitar lessons tailored to every skill level, music genre, and playing style. Click here to learn more.

Dave Isaacs has established himself as a guitar teacher extraordinaire, having built a strong set of educational curriculums for beginner, intermediate, and advanced guitar players alike. Dave shares his expertise largely through video platforms, but also through his thoughtful writing. You can take guitar lessons from Dave Isaacs via his comprehensive video guitar courses on JamPlay.com.

Share this

Become a JamPlay member for unlimited access to 7000+ guitar lessons and 120+ artists and instructors. View membership plans ›

Related Posts

5 Tips For Sitting In (On A Jam Session)

5 Tips For "Sitting In" (On A Jam Session)

“Sitting in” means getting up to play with an established group as a guest.

Years ago I had the opportunity to sit in with the legendary Les Paul at his long-running regular gig at the NYC jazz club Iridium.

I was, of course, terrified, but eager to prove myself. Les introduced me by saying from the stage “there’s a kid here who says he can play”. When I walked up, he asked me what I wanted to play. I called Jimmy Smith’s “Back At The Chicken Shack”, a blues-jam standard. Given the opportunity to join in with a legend like that, I wanted to be in somewhat familiar territory. Twelve bar blues, three chords. I also knew the head melody and was prepared to lead it.

I heard later that if Les didn’t like you, he would just turn up and play over you. But instead he sat smiling and nodding, and I got a lifetime memory.

Now, I was fortunate that I was able to call the tune myself, and so wasn’t at the disadvantage of having to pick it up on the spot. As often as not, you won’t know the tune, and you’ll need to figure it out onstage.

Have you ever wondered how some people are able to jump right in and play along with a song they’ve never heard?

Good musicians can communicate without needing to speak. The ability to do this comes from active listening: reacting and responding in the moment. Familiarity with the “language” – the vocabulary that defines a musical style – is just as important. Once you know the basic vocabulary of a genre, every musical move suggests a set of possible next moves. This is why blues jams are so popular: there’s a common set of norms that are easy to follow.

Once you’ve learned a handful of blues songs, you know to listen for the move to the 4 chord. It’s often predictable (rewardingly so, when you nail it). That move is likely to be signaled by one of the other players on the stage. It might be a walk from the bass player, or a drum fill. It may have been planned and expected, or it may not. Either way, that musical interjection is a “heads-up” that a change is coming.

When you’re sitting in, this is what you listen for most.

You should be aware of the chord changes, but also the energy and dynamics of the other players and how they interact. The interplay of their parts will help you keep your place in the form and anticipate when a new section is coming. This means your first job is not to play right away, or at least, not to play very much. Lay back and listen first. Even if you can’t tell what the chords are at first, you can listen for when they happen. Listen for cycles and patterns. This is the architecture of the song, the structure. Understanding a song’s structure helps you follow the map, and know when to expect a possible new change.

“Understanding” in this case doesn’t even necessarily mean naming the chords. You also don’t need to know the theory to listen for chord changes. Paying attention is enough to begin to notice how certain chord changes are familiar and predictable. The more you listen this way, the more you’ll start to hear.

Ok, so you’re tuned up and tuned in and ready to jam! Here are some major do’s and don’ts.

1. Rule number one (that goeth before all others): when in doubt, lay out.

No one wants to listen to you fumble for the key. If you’re unsure, don’t play.

2. DO ask for the key if you aren’t sure. DON’T assume that means you know all the chords to expect.

Remember that “key” in popular music tells you the tonal center, and not necessarily whether you’re going to use strictly diatonic chords. Keep your ears open and if you’re unsure, hang back. You really don’t need to play through the entire song: pick your moments.

3. Watch your volume. Blend into the group until it’s time to step forward.

The last thing you want is to call negative attention to yourself. Be part of the background until it’s your turn. Good players are able to weave in and out, contributing flavor for a moment and then seamlessly melting back into the group sound.

4. When you do play something, commit. Play with authority or don’t play at all.

That doesn’t mean playing something fancy. We all know how the greats can be commanding with one note. Placement, attitude, and tone matter more than the scale you’re playing.

5. Watch and listen for cues! If you’re given a solo, be able to follow the form so you know when to expect the cue that signals whether or not you’ll get another chorus.

This applies in any setting, soloing or not. I’ve been on stage with alleged pros that suddenly seemed to believe they had a psychic ability to know where the song was going…and didn’t. It detracts from the performance, annoys the band, and makes you look clueless.

Remember, being asked to sit in is an honor, a statement of trust that you won’t screw things up. So treat the stage and everyone on it with respect.

Interested in more guitar lessons and courses? Check out JamPlay.com. JamPlay has over 450 guitar courses from 120+ instructors, and online guitar lessons tailored to every skill level, music genre, and playing style. Click here to learn more.

Dave Isaacs has established himself as a guitar teacher extraordinaire, having built a strong set of educational curriculums for beginner, intermediate, and advanced guitar players alike. Dave shares his expertise largely through video platforms, but also through his thoughtful writing. You can take guitar lessons from Dave Isaacs via his comprehensive video guitar courses on JamPlay.com.

Share this

Become a JamPlay member for unlimited access to 7000+ guitar lessons and 120+ artists and instructors. View membership plans ›

Related Posts

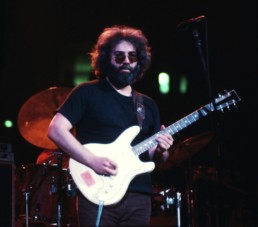

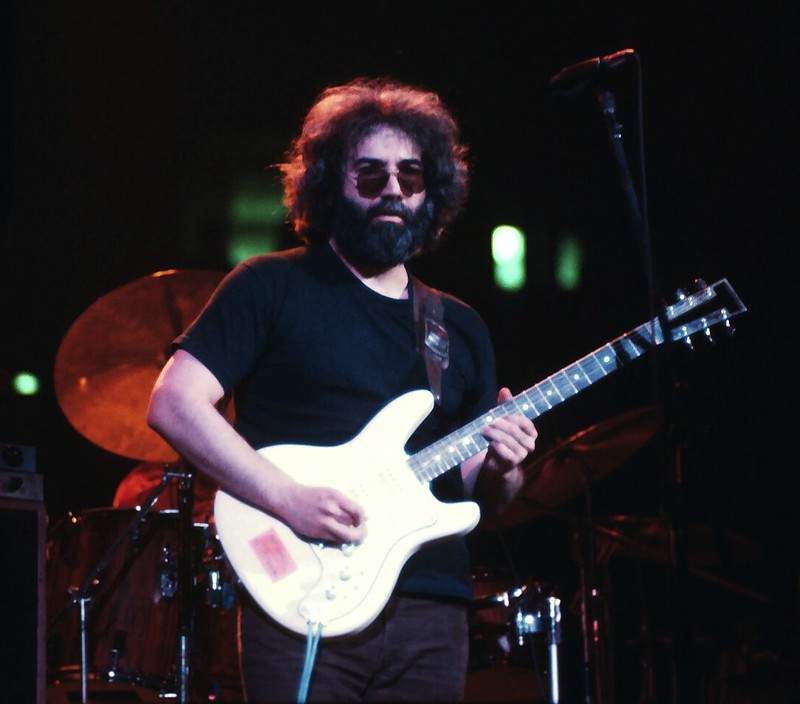

Jerry Garcia and His Bluegrass-Influenced Picking

Jerry Garcia and His Bluegrass-Influenced Picking

It’s been said that a guitar player’s personality comes through their picking attack.

Take a moment to think about it and you’ll see how true that is. Tone is a product of the instrument (and connected electronics) but even more so the player’s touch. Think of what makes Hendrix sound like Hendrix, or Van Halen like Van Halen. When I was younger, that aggressive attack was everything I wanted a guitar to sound like. But then in my first year of college I discovered Jerry Garcia and the Grateful Dead.

Garcia is also among the iconic players whose tone is instantly recognizable.

Like many of the self-taught greats, his technique was idiosyncratic. A jug band banjo player turned guitarist, Jerry’s playing never lost the crystalline definition of the banjo – even on electric guitar.

Of course, banjo picking and flatpicked guitar playing are two totally different things. But tone is equal parts equipment and anatomy: the same hand makes the sound. In Jerry Garcia’s case, his picking hand was (legendarily) missing half the middle finger because of an accident in his youth. Is it possible that this affected the balance of the picking hand, and contributed in some form to his distinctive tone? We’ll never know for sure, but there are certainly echoes of the crisp, bright tone of a banjo in his guitar playing.

What we CAN say for certain is that Garcia’s tone was the byproduct of a light touch.

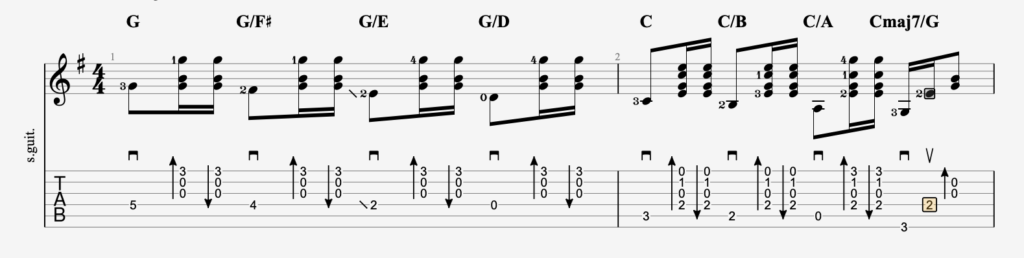

You can hear this all though the Dead’s music, but the flatpicked acoustic opening of American Beauty’s “Friend Of The Devil” is a great specific example. Most of the song is built around a descending G major scale combined with strummed chords, in quintessential country “boom-chick-a” rhythm.

First, a quick note on the fretting hand. The opening G note is played on the D string at the 5th fret with the ring finger. The high G note of the G chord is held at the 3rd fret of the high E with the index finger. This keeps that opening note robust and full, and matches tone better with the rest of the descending scale. Pay attention to the fingering shift into the 3rd chord. It’s also worth mentioning that despite all the left-hand fingering changes, the pattern really is just two chords, G and C against a descending bass.

The rhythm is a simple two-step, with an answering upstroke: one AND-a two AND-a. The accented “and” evokes a bluegrass backbeat “chop”, while the full strum also references a Johnny Cash-style “train beat”.

The challenge of this part is balancing a strong flatpicked downbeat on a single note with a lightly brushed alternating chord. The strummed rhythm has to maintain the sense of backbeat without overwhelming the single notes of the descending scale.

Ordinarily, you would expect a strummed chord to be louder than a single picked note. Here, we’re aiming for the opposite. A strummed chord rings most clearly when the strum “follows through”, meaning that the hand continues past the strings. Strum a chord and try only letting the strumming hand to move as far as the first string. Then try again, allowing the hand to keep moving. You can accomplish this with an arm swing from the elbow, or a twist of the forearm. Either way, the point of the pick moves THROUGH and PAST the strings, setting them in motion as it brushes across it. The pick doesn’t “strike” or “pluck” the string, but glides across its curved surface. This is a really useful mental picture, because the sensation of “brushing” the strings lends itself to a lighter touch.

Try strumming the “boom chick-a” rhythm again, concentrating on the follow-through and the feeling of lightness.

Now pay attention to the attack on the single-note descending line. In contrast to the light, transparent sound of the brushed chords, the single notes need to be robust and clear. This requires a little more weight behind the attack. Instead of playing harder, experiment with putting the forearm into the pick stroke. This requires a more level wrist, as we want to use the entire forearm as our lever. But instead of using the muscles of the arm to push, use the mass of the arm to lean on the string. There’s a big difference between pushing through a string and balancing the pick on it as it slides past.

The strumming movement itself then has two parts and two hand alternating hand positions: level wrist for the bass note, rotating wrist for the chord brush.

If you’re accustomed to resting or anchoring your picking hand, this might feel strange. If you’ve been taught that efficiency of movement always comes first, this might seem wrong. But it’s a great example of how flexible technique leads to more flexible musicianship. The ability to alter your pick attack gives you far more expressive possibility.

For a deep dive into “Friend Of The Devil”, click here to take a look at this JamPlay lesson featuring Tyler Grant and myself teaching the song in detail!

Interested in more guitar lessons and courses? Check out JamPlay.com. JamPlay has over 450 guitar courses from 120+ instructors, and online guitar lessons tailored to every skill level, music genre, and playing style. Click here to learn more.

Dave Isaacs has established himself as a guitar teacher extraordinaire, having built a strong set of educational curriculums for beginner, intermediate, and advanced guitar players alike. Dave shares his expertise largely through video platforms, but also through his thoughtful writing. You can take guitar lessons from Dave Isaacs via his comprehensive video guitar courses on JamPlay.com.

Share this

Become a JamPlay member for unlimited access to 7000+ guitar lessons and 120+ artists and instructors. View membership plans ›

Related Posts

Restarting practice after an injury

Restarting practice after an injury

A hand injury can be an existential crisis for a guitar player.

I had the misfortune of slipping on the ice on Christmas Eve, landing by my outstretched left hand. (Vocabulary word of the day: ER doctors call that a Foosh, Fall On Out Stretched Hand).

It could have been a lot worse. I sustained two small fractures in the bones at the base of my index finger. Treatment has consisted of wearing a brace, and basically laying off my guitar.

It’s important that I offer this disclaimer now. I am not a doctor, and I have no medical training:

If you suffer an injury yourself, follow your medical professionals’ advice.

This piece is about what to do once you’ve been given the all clear to start playing again. Warming up is always important, but even more so after a period away from the guitar. When I asked my doctor about it, his advice was to let pain be the guide.

Patient: hey doc, it hurts when I do this.

Doctor: so don’t do that!

If you’re still young and indestructible, you might not think any of this applies to you. But remember, guitar playing is athletic for the hands. Athletes who don’t train properly hurt themselves. More positively, this mindset builds the kind of fluid control every guitarist is aiming for.

If you haven’t played in a while, your muscle memory is still there, but we need directed control too. Without control, muscle memory movements are like a twitch: nothing but impulse to move. Tuning in to sensation and touch creates a more complete mental picture of what your hands are doing, beyond just where the finger sits. That complete mental picture is what leads to real control.

Let’s take a moment to look at an x-ray of the hand:

Notice how the bones of the fingers and thumb extend all the way back to the base of the hand.

So your fingers don’t end at the knuckle but continue back to the bones of wrist. When palm is relaxed, the whole system is more open and the fingers move more freely. Similarly, your thumb extends all the way to the base of the wrist.

It’s very easy to miss this point, but it’s crucial. If your thumb is pressing on the back of the neck, that pressure compresses the center of the hand. Try this without a guitar and you’ll find it MUCH harder to move the fingers freely when the thumb is pushing down. Since many if not most students apply much pressure with the fret hand thumb, it’s possible your muscle memory could use the reset.

Returning to your guitar with this gentle tuning in to the sensation of touch is also a great opportunity to reprogram bad technical habits.

Just remember to start off easy. Don’t play a song, or a scale. Touch one note. Pay attention to the pressure on the fingertip, letting it rest on the string rather pushing it down. This is a good way to warm up under any circumstances, because you’re not just warming up the muscles. You’re also making a tactile, brain-to-finger connection.

Try this as a visualization exercise:

When the the hand is relaxed, the fingers should naturally curl. Imagine the bones of the fingers running up through the hand, and try to feel the space between them. Relax the base of the thumb and allow the palm to open. Imagine the hand broadening, giving all your fingers more room.

Move your hand to the guitar, maintaining this feeling. Use your arm to bring the hand into position. Keep the base of the thumb relaxed and notice how it naturally allows the fingers to move more freely.

My own practicing lately has consisted of very light and gentle hand movements to start with, working to open chords, and then beginning to work in gentle stretches. The entire time, I am keeping the mental picture of that hand x-ray in my mind. I want to maintain the sense of openness and space between the fingers, and let my arm do the work instead of my hand and wrist. This is, ultimately, the way you always want to warm up, but it’s especially important when you’re rebuilding.

In the long run, this kind of practicing will make you a better player and less susceptible to repetitive strain.

Also remember that when it comes to playing an instrument, “no pain no gain” is NEVER the right mindset. Your body will tell you when it’s being overtaxed, as long as you learn how to listen to it.

Interested in more guitar lessons and courses? Check out JamPlay.com. JamPlay has over 450 guitar courses from 120+ instructors, and online guitar lessons tailored to every skill level, music genre, and playing style. Click here to learn more.

Dave Isaacs has established himself as a guitar teacher extraordinaire, having built a strong set of educational curriculums for beginner, intermediate, and advanced guitar players alike. Dave shares his expertise largely through video platforms, but also through his thoughtful writing. You can take guitar lessons from Dave Isaacs via his comprehensive video guitar courses on JamPlay.com.

Share this

Become a JamPlay member for unlimited access to 7000+ guitar lessons and 120+ artists and instructors. View membership plans ›

Related Posts

Play More of the Music by Playing Solo Guitar

Play More of the Music by Playing Solo Guitar

Solo guitar melody arrangements are a fun and satisfying way to play more of the music by yourself.

Working up an arrangement also helps pull all your guitar knowledge together. The process of arranging a song is a series of choices: which chords to fit to the melody, and how to voice them on guitar. This requires some knowledge of theory and of the fretboard!

Let’s start with establishing three basic principles:

- A melody is a sequence of notes expressed over time.

- Notes of the melody will belong to (and often imply) the underlying chords.

- There are always multiple ways to harmonize a melody, by varying the chords and when they change.

We also should establish that a basic major or minor chord contains just three notes.

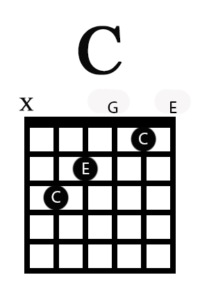

Many guitar chords contain four, five, or six notes, in which notes are doubled at the octave. For example, a familiar open position C major chord contains the three notes of a C triad, C-E-G, and adds another C and E an octave higher:

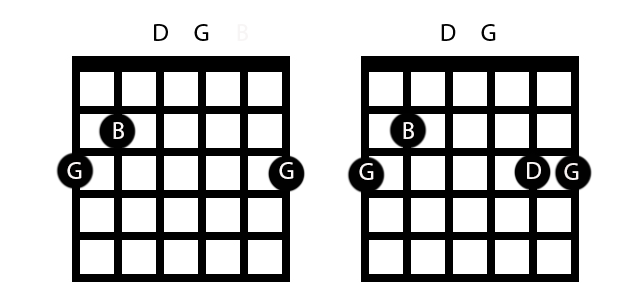

The G major triad is G-B-D, but a familiar open G chord has three G’s, and doubles either the B or the D depending on the fingering:

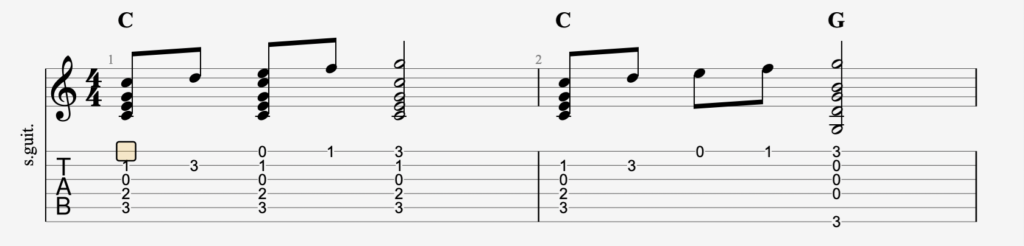

In the next example below, it’s easy to hear how the opening C chord blends with the starting melody note C.

Note how the same chord blends equally well with the third and fifth tones of the series, E and G, because a C triad also contains those two notes as well. So we might say that the C chord harmonizes with the notes C, E, and G. The scale segment therefore contains the notes of the C chord plus two passing tones, connecting steps between chord tones.

C d E f G

The D and F notes do NOT belong to the C chord. So technically they should clash, but they fall on between the chord tones on the weak beats. So the entire scale segment fits the C chord, even though it contains notes that don’t belong to the chord.

Note that the second bar substitutes a different chord on the 5th tone, G. It should be no surprise that a G chord would fit a G note, of course, and in the key of C we would then refer to it as a 5 chord. This is a tension, an open-ended question that demands a resolution. Think of the 5 chord as a musical comma, setting up expectation for the next phrase.

Since the same note can appear in more than one chord, we’re not even obligated to start with a C chord to match the C note.

Remember our basic chord theory in its simplest form. To find a triad, pick a note and then skip a letter twice:

A C E

B D F

C E G

Etc.

Of course, you may need to adjust for sharps and flats, and this is why learning key signatures is so helpful. Over time, learning multiple songs in the same key will help you remember. In this case, we’re in C, so there are no accidentals needed:

C D E F G A B C

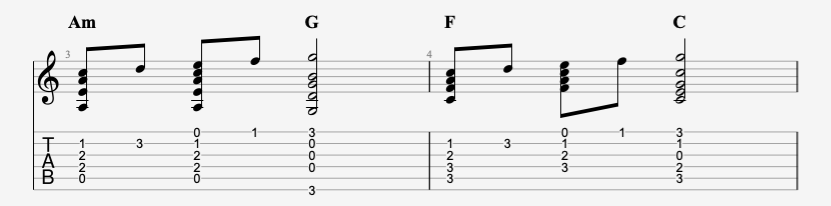

Looking at this, you might notice that the note C is a third above A. In other words, if A is note one, C is note 3 in the sequence: the third of the chord. This implies an A minor chord, and gives us the opportunity to reharmonize the first note:

Notice how in the second bar, the same C note is now reharmonized by an F chord. So the note C fits the C, Am, AND F, chords because it forms the root, third, and fifth respectively.

You might also notice that in the second half of this bar, the F is used to harmonize an E. While this might seem odd at first, look at the notes of an F triad, F – A – C. If we continue the pattern and skip ANOTHER note, we get F – A – C – E, or an Fmaj7.

This opens up an entire new set of possibilities, because now we know that a single note can comfortably belong to at least four chords!

If you’re up for a challenge, check out this fun example of how substituting diatonic chords can make a familiar melody sound very different. Note the use of chords like Ab, E7, and Eb, none of which belong to the key of C – but all contain at least one note that does. So the unusual chords fit but in a very unexpected way! Have fun.

Interested in more guitar lessons and courses? Check out JamPlay.com. JamPlay has over 450 guitar courses from 120+ instructors, and online guitar lessons tailored to every skill level, music genre, and playing style. Click here to learn more.

Dave Isaacs has established himself as a guitar teacher extraordinaire, having built a strong set of educational curriculums for beginner, intermediate, and advanced guitar players alike. Dave shares his expertise largely through video platforms, but also through his thoughtful writing. You can take guitar lessons from Dave Isaacs via his comprehensive video guitar courses on JamPlay.com.

Share this

Become a JamPlay member for unlimited access to 7000+ guitar lessons and 120+ artists and instructors. View membership plans ›

Related Posts

Guitar Resolutions for the New Year

Guitar Resolutions for the New Year

Make this the year your resolutions lead to some musical resolution.

In this age of the internet guitar multiverse, you could easily see more lesson content in a single day than you could absorb in a year. Having so resources at your fingertips is a fantastic asset. Had YouTube and JamPlay been available in 1980, I may never have left the house as a teenager! But it’s also easy to be overwhelmed by the sheer amount of data.

These three suggestions will help make it easier to stay on task and make your practicing more powerful. Make them your musical resolutions for 2023.

1. Concentrate on the music that moves you.

When asked about their specific musical goals, most people will say they “just want to get better”. But unless you have the time and motivation for a broad and comprehensive practice routine, that kind of open-ended thinking can also take you down a rabbit hole.

Everyone has particular styles and sounds that appeal to them most. So it makes sense to focus on music you love. Ultimately, you can learn the fundamentals from any genre: the differences are a matter of vocabulary and flavor.

A working professional musician may have a wide enough vocabulary to play in multiple styles, but many if not most of the artists that inspired us all growing up played primarily one. That’s not to say you shouldn’t learn from different styles of music, but recognize that the greats all knew their territory inside and out. The more thoroughly you know a particular song or style, the more satisfaction and confidence you’ll get from playing it. Real fluidity comes with familiarity.

Find the roots of the sounds you love and study those. Feeding the love can be your strongest motivation.

2. Supplement that practice with detail work.

“Detail work” includes anything from finger patterns and scales to isolated passages from a song. Often, this means going slowly enough to be consistently accurate. If you consistently miss a note, there’s a mechanical reason why. Slowing down eliminates a lot of extraneous effort and lets you concentrate on accuracy. This lets you sidestep any bad habits while reinforcing how well you know the music.

If that means playing so slowly that you don’t hear the song any more, that’s ok. Concentrate on precision first, then build up the tempo in increments. You will likely find that playing slowly can actually be harder, because there’s so much space between beats. But it’s great ear training for hearing (and feeling) subdivisions of the steady pulse.

Use a metronome or drum loop to make sure you keep steady time.

Then play the same passage without it and see how well you can stay in tempo. You can also practice the same tempo with different metronome settings. For example, one note per tick at 120 bpm is the same tempo as two notes per tick at 60, but it won’t feel the same to play. This helps fine-tune your sense of time along with your accuracy.

3. “Move the needle”.

When you sit down to play, do you have a goal for that day’s practice? Of course one goal is to get from the first note to the last without a mistake. Developing that kind of smoothness takes time, lots of detail work, and conscious repetition.

Given what a large task that really is, your expectation for every practice session should be to “move the needle”: to advance something forward in some way. That might mean finishing the session being more familiar with even one detail than you were when you started. Be clear on what you’ve accomplished, even if you lose it the next day. It’ll be back and come together faster each time, until one day it’s just there. The brain needs time to absorb and “consolidate” the movements you teach the body when you practice, so blind repetition doesn’t move you forward. But conscious repetition moving towards a limited, attainable goal reinforces and strengthens.

Your progress becomes clearer as you meet one attainable goal after another. These goals might be tiny, but accumulate over time.

If we condense these three ideas down the their simplest form, it might read like this:

- Feed the love

- Pay attention to the details

- Take the long view.

Sounds like the formula for any successful relationship.

Interested in more guitar lessons and courses? Check out JamPlay.com. JamPlay has over 450 guitar courses from 120+ instructors, and online guitar lessons tailored to every skill level, music genre, and playing style. Click here to learn more.

Dave Isaacs has established himself as a guitar teacher extraordinaire, having built a strong set of educational curriculums for beginner, intermediate, and advanced guitar players alike. Dave shares his expertise largely through video platforms, but also through his thoughtful writing. You can take guitar lessons from Dave Isaacs via his comprehensive video guitar courses on JamPlay.com.

Share this

Become a JamPlay member for unlimited access to 7000+ guitar lessons and 120+ artists and instructors. View membership plans ›

Related Posts

Guitar Practice: Touch and Tone

Touch and Tone

The best compliment I ever got on my tone was from the producer on a recording session.

He said, “you’re the only guy I know who can make a Gibson sound like a Fender”.

He didn’t mean that he liked Fenders better than Gibsons. He meant that he heard the tone, not the guitar.

Playing a different guitar can be like putting on a different mask. Playing a country song? Pick up a Telecaster. Channeling Stevie Ray Vaughan? Only a Strat will do. Of course the sonic quality of each guitar IS part of the sound of a particular style or artist. And if you’re really trying to nail a particular player’s tone, knowing their signal path from fingers to speaker is part of the picture. But no amp, pedal, or new guitar is going to make you sound just like your heroes.

“Your tone is your face. Why would you want to look like someone else?” – Carlos Santana

Eddie Van Halen talked about learning to make different sounds by just hitting the guitar different ways, because he couldn’t afford to buy lots of gear. Of course, he did make technical changes to his rig itself. But his sound was more than the gear, it was in his hands. Just give a listen to “Spanish Fly” and it’s obvious who it is. Even on an acoustic guitar without his usual setup, EVH sounded like EVH. Stevie Ray Vaughan on a 12-string acoustic on “Life By The Drop” is totally recognizable without his signature Strat sound. The instrument and amp and signal path are only part of the story. The proportion of your fingers and hands, the shape of the instrument you play and how it lays on your body – even the way you hold the guitar has an impact on tone.

Developing your touch means educating your picking hand.

Learn to be more aware of your picking hand attack, and notice how the string FEELS as you move through it. Pay attention to the tactile feedback, gauging how much resistance you feel from the string and the way it responds. Are you pushing the string out of the way, snapping it from underneath, or just gliding across the surface? Each of these is a different movement and a completely different sound.

If you always play plugged-in with effects, you might be masking this relationship.

You might be surprised how much you can learn about touch from an unplugged electric guitar. The increased dynamic and tonal control you get from practicing “naked” also allows you to use effects more expressively.

Your choice of string gauge and pick is part of this puzzle too, of course. Changing either changes the resistance equation, and tactile feedback helps you adjust accordingly. I used to use light picks on heavy strings because my right hand was so heavy. Over the years I’ve gone to lighter strings and heavier picks, which requires a light touch and a lot more control. But I find that the lighter my touch gets, the better my sound is.

A heavy-handed attack has a sound of its own and might be the right thing in some settings. But that heaviness might have a lot more to do with the size and proportions of the player that hand belongs to.

At the end of the day, your rig is like a suit you put on.

It’s style, fashion, and self-expression. A set of choices a player presents to the world that was something about who they are. But to be more than an empty suit, develop the voice of the player inside. That starts with touch.

Interested in more guitar lessons and courses? Check out JamPlay.com. JamPlay has over 450 guitar courses from 120+ instructors, and online guitar lessons tailored to every skill level, music genre, and playing style. Click here to learn more.

Dave Isaacs has established himself as a guitar teacher extraordinaire, having built a strong set of educational curriculums for beginner, intermediate, and advanced guitar players alike. Dave shares his expertise largely through video platforms, but also through his thoughtful writing. You can take guitar lessons from Dave Isaacs via his comprehensive video guitar courses on JamPlay.com.

Share this

Become a JamPlay member for unlimited access to 7000+ guitar lessons and 120+ artists and instructors. View membership plans ›