Triads and Melody

Guitar Practice: Triads and Melody

Triads are chords in their simplest form.

You might think that the “box” forms you learned early on are the simplest ones, but any major or minor chord only requires three notes. When a beginner learns a C chord on piano, it’s almost always introduced as a triad: C-E-G, with the right thumb on middle C. The standard open position C chord contains 5 notes, two of them doubled: C – E – G – C- E.

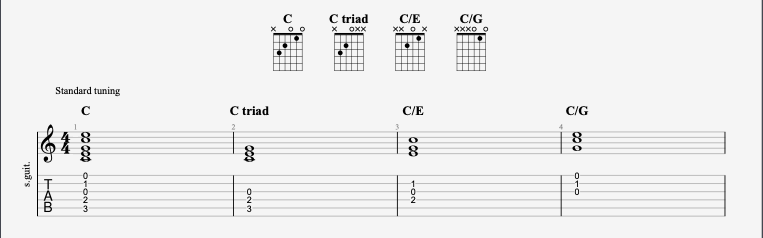

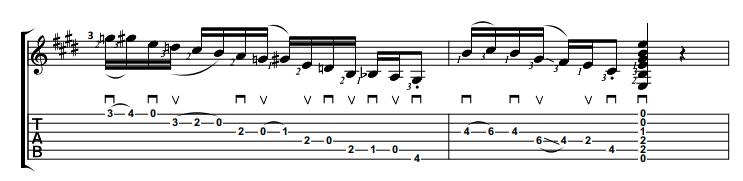

Taking a closer look, you might notice how this big chord contains three overlapping versions of the C triad:

(Be sure to look at the notation too, not just the tab. Even if you don’t read music, it helps to see the movement of the individual notes).

The three triads all contain the same notes in 3 different orders, but always in sequence (low to high): C-E-G, E-G-C, and G-C-E. Each triad lives on its own set of three adjacent strings. The diagrams distinguish the names by the bass note, but it would be equally correct to call them all C chords.

Without going too deep into the math, let’s just say for now that we can build a triad by starting with a root and then skipping a letter twice: C to E to G. In the key of C, we don’t need to include any sharps or flats:

C D E F G A B C

The C triad is formed by the first, third, and fifth notes of the C major scale.

If we apply this formula using each of the seven tones as a root, we get a set of seven diatonic triads:

C major: C E G

D minor: D F A

E minor: E G B

F major: F A C

G major: G B D

A minor: A C E

B diminished: B D F

“Diatonic” means that we pull the notes directly from the source scale or C. This creates a sequence of chord qualities, major, minor, or diminished. This is a topic worthy of its own article and much more. For now, we’re just going to work with three major triads: C, F, and G.

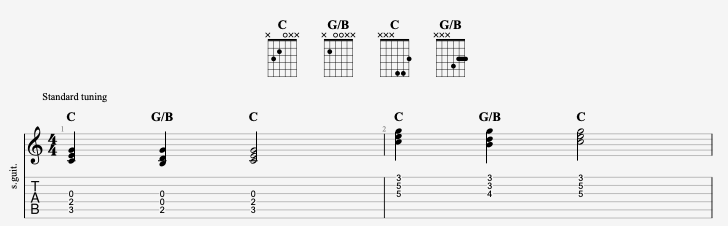

When our hypothetical piano student first encounters a G chord, it might appear like this. The root position G triad is spelled G-B-D, but notice that here B is the lowest note. This is an example of voice-leading: keeping the tones of each chord as close together as possible.

The G chord is spelled G-B-D. So why introduce it with B as the lowest note? This is an example of voice-leading triads: keeping the tones of each chord as close together as possible.

When we string chords together, each note is like a voice in a choir.

If we keep all the chords in root position, it looks and sounds like this:

There’s nothing wrong with the way it sounds. But you can see how the entire triad jumps up or down, with all three voices moving together. Looking back at the first example, you can see and hear how the notes stay closer together. The G note, root of the G triad, is on top because it’s a common or shared tone with the G note in the C triad. The other two voices drop to the next scale tone:

string 1: G —- G —- G

string 2: E —> D —> E

string 3: C —> B —> C

Voice leading allows you to make chord changes more melodic.

Many great classic rock riffs are memorable for their melodic use of triads: listen to “Panama” by Van Halen, “Free Ride” by Edgar Winter, “Run Like Hell” by Pink Floyd, “Turn It On Again” by Genesis, or “The Wind Cries Mary” by Jimi Hendrix. Besides being fun, learning familiar songs gives you examples of how triads are used on guitar. But it’s also really helpful to do drills that make you think through the shapes you’ve learned.

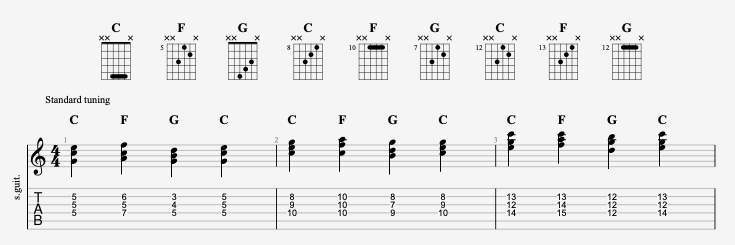

For example, this exercise walks through C-F-G-C using three triad forms on the same string set. Practice this slowly, out of time, concentrating on the voice-leading. Notice how each string forms its own melody, and listen for each one.

Mixing these up gives us different melodies on each string, but all the chord changes remain fluid.

Your ultimate goal is to be able to play any triad in any position on any string set, but don’t try to memorize everything at once! This exercise uses just three shapes, and puts them in a musical context. Use this as a model and try the same chord sequence in another key. Or put the same chords in a different order. Even if your goal is simply to play your favorite songs, exercises like this help you do that by reinforcing how well you know your way around your guitar.

Interested in learning to solo on guitar? Check out JamPlay.com. JamPlay has over 450 guitar courses from 120+ instructors, and online guitar lessons tailored to every skill level, music genre, and playing style. Click here to learn more.

Dave Isaacs has established himself as a guitar teacher extraordinaire, having built a strong set of educational curriculums for beginner, intermediate, and advanced guitar players alike. Dave shares his expertise largely through video platforms, but also through his thoughtful writing. You can take guitar lessons from Dave Isaacs via his comprehensive video guitar courses on JamPlay.com.

Share this

Become a JamPlay member for unlimited access to 7000+ guitar lessons and 120+ artists and instructors. View membership plans ›

Related Posts

Guitar Practice: Conscious Repetition

Guitar Practice: Conscious Repetition

“Don’t practice till you get it right, practice till you can’t get it wrong”.

It’s well-intentioned advice, but it might give you an incomplete picture. Many people will read that sentence as, “do it over and over until it’s perfect”. But playing well doesn’t come from repetition alone.

The best players put in their time out in the proverbial woodshed, and you can be sure they got their reps in. But that’s not what makes them the best. It’s not talent either, because plenty of talented people stop growing when they reach the limits of their gift.

The best players are dynamic in that they make the music “speak”.

Think of every note as a spoken word, and every phrase a sentence. If you’ve ever heard two different actors recite the same lines with two very different results, you know that delivery is really what drives the meaning home. So accurately hitting a target is only part of the picture.

The purpose of repetitive practice is to ingrain a movement into what we call muscle memory. Muscle memory doesn’t require conscious thought but an unconscious trigger. (You don’t have to think about putting your foot on the brake pedal when you need to stop your car). When we perform a movement repeatedly, the brain reinforces the specific pathways it requires, creating a kind of neural superhighway. This is happening at the speed of electricity, so it’s impossible to get ahead of it consciously. But like a Porsche on the Autobahn, your body can respond like the finely tuned machine it is.

The subtleties of articulation and dynamics that bring music to life ARE muscular as well.

A slide feels different from a hammer-on and requires a different movement. Playing louder or softer requires a change in the intensity of your attack. So all musical playing is technical, in that you have to perform an action to get the effect. But expressive actions should be conscious, at least potentially. You might have practiced a crescendo carefully to make sure you build your volume at the right speed, but your musical mind still has to be engaged to execute it well.

Expressive are thoughts and gestures. These can be memorized just like anything else, but they should never be automatic. Instead, your goal should be complete familiarity with the music. You know exactly what needs to happen in that moment and you have the technical ability to execute the move. But the action itself is a choice.

If you’ve ever jumped off a high diving board, you might remember what that first time felt like. Once your feet left the board, how you landed was up to gravity and chance. But over time, you can learn to control the dive. Your time in the air isn’t just free-fall, but the predictable result of good form and focused attention. Guitar is no different.

No amount of repetitive practice is going to make you an expressive player without directed control.

The muscles may have been prepared and that neural superhighway paved and ready. But the thought is what delivers the message to the fingers.

So the goal of repetition is not to become automatic. The goal of repetition is to become so familiar with the music that your hands AND mind know where you are at all times. That means engaged practice, paying attention to detail. Most of all, it means your practice is never mindless. Don’t repeat casual sloppiness. If you can’t execute something cleanly, take a closer look and find out why. Odds are good that the problem might be one of missing or incomplete data. If you don’t know what’s going wrong other than the fact that it’s not working, repetition alone will not solve the problem.

Does your technical practice need a reset? This course is designed to do just that.

Interested in learning to solo on guitar? Check out JamPlay.com. JamPlay has over 450 guitar courses from 120+ instructors, and online guitar lessons tailored to every skill level, music genre, and playing style. Click here to learn more.

Dave Isaacs has established himself as a guitar teacher extraordinaire, having built a strong set of educational curriculums for beginner, intermediate, and advanced guitar players alike. Dave shares his expertise largely through video platforms, but also through his thoughtful writing. You can take guitar lessons from Dave Isaacs via his comprehensive video guitar courses on JamPlay.com.

Share this

Become a JamPlay member for unlimited access to 7000+ guitar lessons and 120+ artists and instructors. View membership plans ›

Related Posts

Another Way to Think About Guitar Modes

Another Way to Think About Guitar Modes

Guitarists spend a lot of time talking about modes.

Learning modes usually starts with a list of scale fingerings, and for a lot of people it never goes any further than that. For those that take the next step, there’s the math (theory) that determines which mode to use over a particular chord.

Those scale fingerings do have a purpose in introducing different sonic flavors. The theory gives you a way to categorize those flavors so you can use them intentionally. But learning those fingerings doesn’t get you there on its own. So what’s missing?

Every scale has a recognizable sound.

We could also say each has a particular flavor, color, feel – any other word that describes the way you perceive the difference between one scale and another.

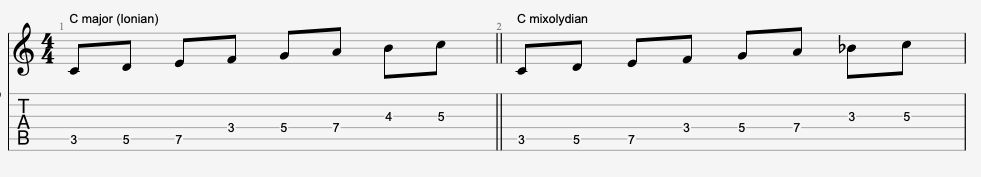

Here are two scales starting on C:

C major scale (Ionian): C D E F G A B C

C mixolydian: C D E F G A Bb C

Notice that the only difference between them is the seventh tone.

In the C major scale, the note is B, and we would call it the 7th of the scale. In mixolydian, we lower the seventh by a half-step. So we might say that the mixolydian mode has a flatted 7th or b7, in this case Bb.

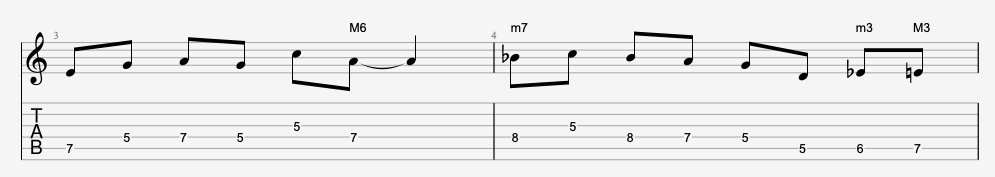

Now play these two simple licks:

If we analyze the first lick, you might recognize a C major pentatonic. The second lick brings in the Bb, but also includes an Eb.

What’s going on here? Weren’t we starting with C major?

Was the major pentatonic a different choice of scale, or just a lick that happened not to include the seventh? And where did that Eb come from? That wasn’t in either scale either.

Every tone of the scale has a particular flavor you can learn to recognize. Odds are, for example, you can hear this in your head as you read. Maybe you can even sing it:

Do re mi fa sol la ti do

These are called solfège syllables and have been used for hundreds of years to help musicians communicate. In the European classical system, “do” always stands for C. That means that as young musicians learn, the syllables become connected to the pitches. This strengthens the players sense of what we might call absolute pitch: knowing that a C is a C just by hearing it. We generally call that “perfect pitch” and most see it as a gift some people are born with. But it’s absolutely something that can be learned. Many people describe different notes as different colors when explaining how they tell the difference.

Music students in the US learn solfège differently. American schools use a “moveable do” system, where “do” is the first tone of any major scale. This reinforces the student’s “relative pitch”, the ability to hear relationships between notes.

This is the skill that lets you differentiate between modes by sound alone.

Every tone of the scale has a recognizable character. The difference between C major and C mixolydian is the difference between the sound of a major seventh or minor seventh. If you play a lick that pulls only some of the notes from C major but does not include the leading tone, we would still say we’re in C major. If you play another lick that includes a B-flat, you’ve arguably only altered one note of the scale rather than shifted gears into an entirely new one. Mathematically, the note actually comes from C natural minor. The relationship between major six and minor seven is a defining flavor of mixolydian. But it’s still just replacing one note with another: Bb instead of B.

The E flat in the second lick doesn’t belong to major or mixolydian, but it still works. The note is borrowed from C minor, an interval of a minor third up from the root. We’re using it as a stepping stone or passing tone to connect D and E. So the E flat doesn’t have to be accounted for in determining what scale you’re playing. We hear it as a set up for a note that does belong to the scale.

There are hundreds of variations of blues, rock, and boogie licks that use this expanded mixolydian sound. This lick incorporates the b7 as, mixed minor and major thirds, and the flatted 5th “blue note” before wrapping up with straight major pentatonic.

You can watch the Jamplay lesson here.

You can apply this kind of thinking to any scale, not just modes. Every tone has a flavor, and every tone has a note next to it that could be added or substituted to change that flavor.

This doesn’t mean you shouldn’t be learning those fingerings as well. But this way of thinking can start building the context that makes them useful. Here’s an introductory lesson on the mixolydian mode, from the “Learning To Lead” course.

Interested in learning to solo on guitar? Check out JamPlay.com. JamPlay has over 450 guitar courses from 120+ instructors, and online guitar lessons tailored to every skill level, music genre, and playing style. Click here to learn more.

Dave Isaacs has established himself as a guitar teacher extraordinaire, having built a strong set of educational curriculums for beginner, intermediate, and advanced guitar players alike. Dave shares his expertise largely through video platforms, but also through his thoughtful writing. You can take guitar lessons from Dave Isaacs via his comprehensive video guitar courses on JamPlay.com.

Share this

Become a JamPlay member for unlimited access to 7000+ guitar lessons and 120+ artists and instructors. View membership plans ›