Why Practice Scales?

Scale work is a basic part of many guitarists’ practice routine.

Teachers routinely assign scales and talk about the importance of “the 5 positions” or “CAGED theory”. This is useful information, to be sure, but many students are still left confused. Why exactly do we practice scales, and how do you use that knowledge to actually learn to solo?

1. Precision and accuracy

The ability to get your fingers to land where you want them to is pretty fundamental to good guitar playing. You can practice facility and accuracy with anything, provided you slow it down enough to stay in control of your fingers. But scales are a good way to develop technical skills because the movements are going to show up in the music you play. The same can’t be said of many pure finger exercises like “spider” patterns. These have their place, but for the most part these exercises are purely mechanical and have no real musical application outside of occasional sonic weirdness. (Which does have its place…check out Jimmy Page’s dissonant signature riff in the Firm’s “Radioactive” from 1985).

2. Fretboard mapping

Guitar is not a linear instrument like a piano. The notes on a single string are, in that moving up the neck one fret at a time walks through the chromatic scale just as striking every key on a keyboard would. While we do often play linear moves along the same string, a scale fingering is going to cross strings. Now instead of moving in a straight line, we’re navigating a matrix.

This means there are multiple paths to the same place.

It’s possible to work through all the different combinations in an organized way, but most people don’t. To be fair, you might not need to. Lots of iconic players used the same patterns again and again, and it didn’t bother them or us. So it’s not necessarily true that you NEED to know every possible variation. The more options you have, the better, but not if it only creates confusion.

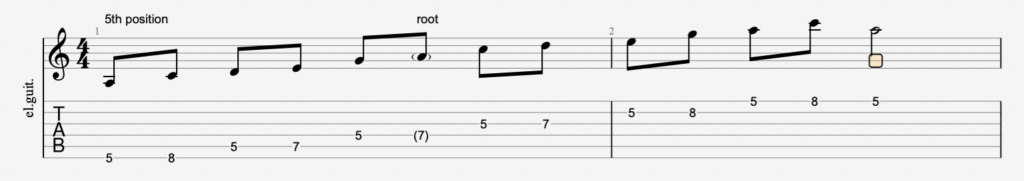

With that said, once you’ve learned one form or pattern, that should help you learn the next one. If you are learning the “5 positions/CAGED” model, it will really help clarify things if you look at each shape as a variation on the last. For example, let’s say you’re starting with a familiar A minor pentatonic in the 5th position:

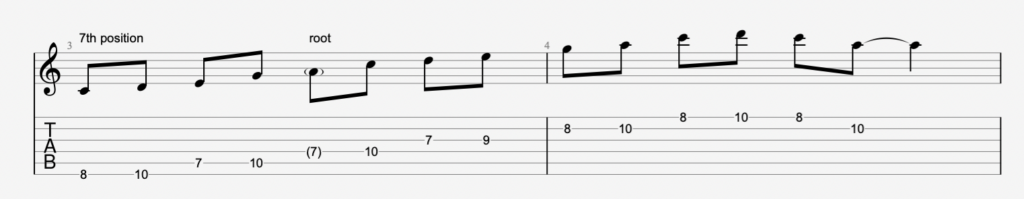

If we’re following the “5 positions model”, the next form would be played in the 7th position:

Rather than learning these as two unrelated things, look for the places the patterns overlap.

Notice the shared root note on the D string (in this case, at the seventh fret). Use this as an anchor or landmark, the same way you might use a 6th string bass note to identify a barre chord.

Try playing simple melodic fragments in both positions, hitting the same notes with different fingering:

Don’t let this be dry, uninteresting work! Playing short scale fragments in different places is absolutely key to developing your fretboard knowledge and mental flexibility. Fluid players have absorbed the fingerings to a point where they think in ideas and phrases and the fingers know how to articulate them. But if all you do is run scales up and down the entire shape, that’s all your hands will know how to do.

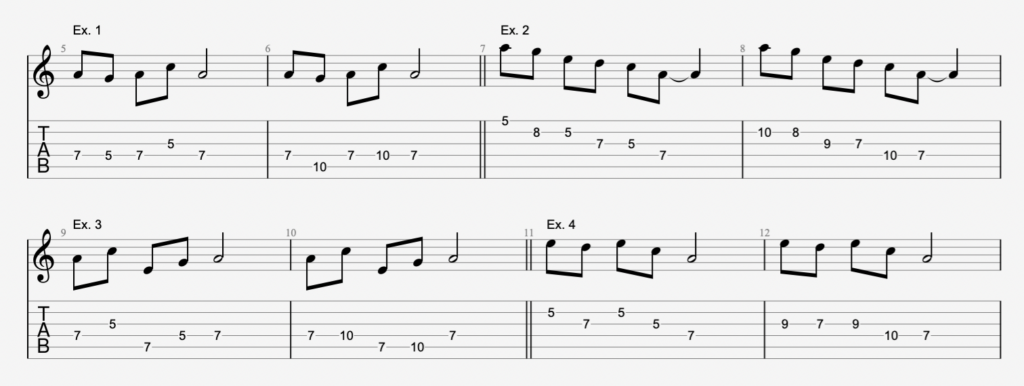

Remember that “licks” are just recognizable combinations of notes from a scale (or combined scales).

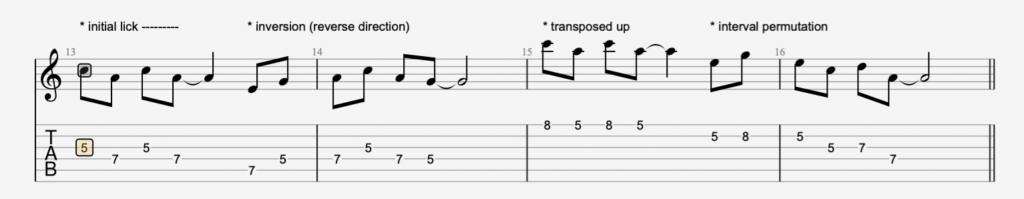

So you need to learn not just patterns but permutations. For example, here are a series of variations on a 4-note lick. They’re all derived from the same minor pentatonic form, and are related either through pitch, melodic shape, or rhythm. These relationships are what make them sound coherent as a series of unfolding variations. The consistent rhythm helps reinforce the sense of call and response, a very natural way of organizing phrases.

3. Ear training

If we’ve established that a scale pattern is a map, it would make sense for us to identify locations along the path. We can do this by note name, and there’s value to that information. But improvising musicians are not thinking of note names. Rather, most are listening to patterns and relative relationships.

An “A” root of a minor pentatonic scale sounds completely different when that same A is the seventh of a Bb major scale.

We learn how to use the scales by identifying the individual notes not by name but by their quality and position in the sequence. This is a long process to master for most people, but it starts with listening. Label the notes as you play patterns: for a minor pentatonic, it’s root, minor 3rd, 4th, 5th, minor 7th. These are recognizable sounds, and the more closely you listen the more commonality you will begin to hear.

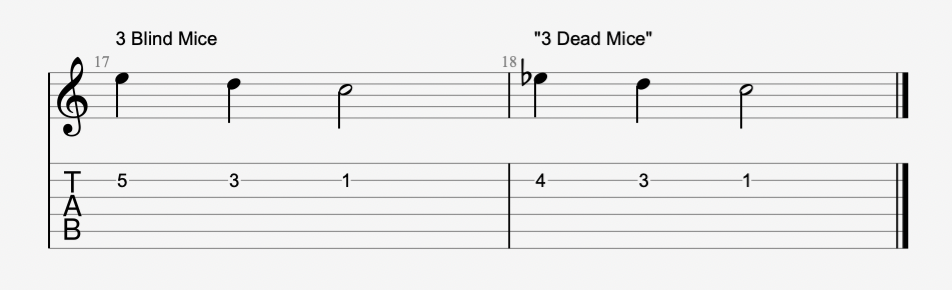

Most people’s ears are more sophisticated than they realize, once they know what to listen for. Rather than thinking of all of this as a series of mathematical formulas, think instead about colors, flavors, and feeling. Listen for tension and release, clash and blend, drama and calm. If you don’t “hear” it, keep listening. I like to use this example when teaching young students the difference between major and minor:

It usually gets a laugh, and it makes the point. You don’t have to be musically educated to listen for the difference between sounds. In fact, the way to get educated is to just start listening.

One great trick is to play scales against a drone (one consistent note).

Here is a useful YouTube playlist you can use for this purpose:

https://youtube.com/playlist?list=OLAK5uy_kQHsbDd1hllwmhD_0MZuhvuIu_P5zLCTI

Playing the scale against the drone lets you hear the differing degrees of tension between different notes of the scale. Try identifying small fragments according to the order of notes in the sequence:

- Root through the 3rd and back (1 2 3 2 1)

- Root through the fifth and back ( 1 2 3 4 5 4 3 2 1)

- Major triad (1 3 5 3 1)

- One octave scale (1 through 8)

If you try this exercise with every scale you learn, you will quickly have a better understanding of the musical elements each contains. The fingering pattern is only the first step of an ongoing process of mental mapping, ear training, and conscious exploration.

Remember, scales are not “boring but necessary”.

Learning scales is one way to get to know the fretboard while developing your facility and your ear. But it’s crucial for that practice to include music, not just locations on a fretboard.

Interested in more guitar lessons and courses? Check out JamPlay.com. JamPlay has over 450 guitar courses from 120+ instructors, and online guitar lessons tailored to every skill level, music genre, and playing style. Click here to learn more.

Dave Isaacs has established himself as a guitar teacher extraordinaire, having built a strong set of educational curriculums for beginner, intermediate, and advanced guitar players alike. Dave shares his expertise largely through video platforms, but also through his thoughtful writing. You can take guitar lessons from Dave Isaacs via his comprehensive video guitar courses on JamPlay.com.

Share this

Become a JamPlay member for unlimited access to 7000+ guitar lessons and 120+ artists and instructors. View membership plans ›