Get More Power From Your Power Chords!

Power chords are part of the backbone of rock guitar.

Tony Iommi’s epic, lumbering sludge on “Iron Man,” and Ritchie Blackmore’s iconic grind on “Smoke On The Water” have been first steps for three generations of players. Malcolm Young’s riffs drove AC/DC into musical history, and James Hetfield’s machine-like right hand is essential to Metallica’s power.

We find power chords in more places than in the obvious heavy rock setting. But first, let’s look at why those simple forms create so much, well, power.

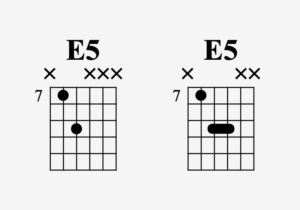

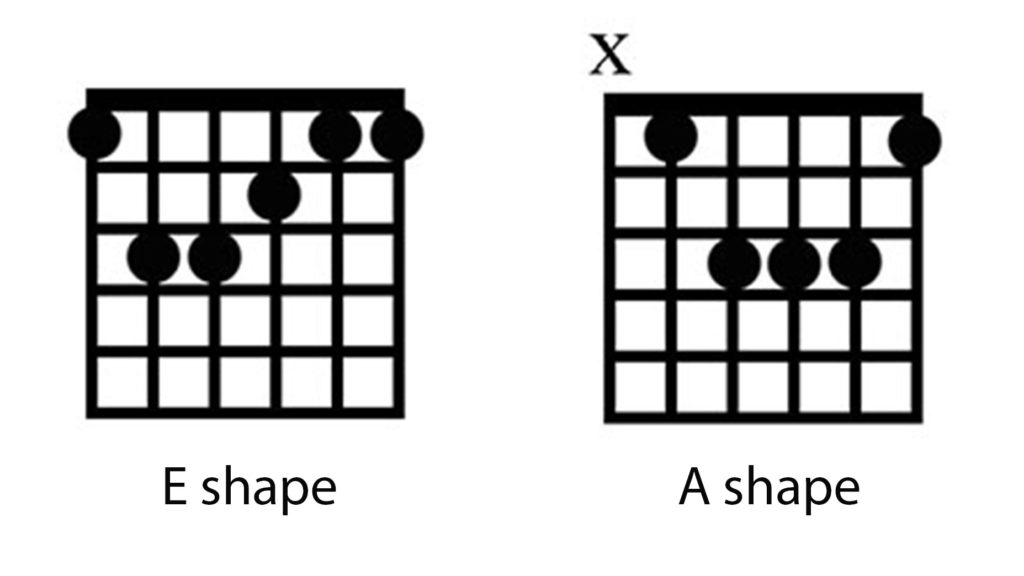

The term “power chord” is sometimes used to refer to the main movable barre chord forms like the six note “E-shape” and four or five-note “A shape”:

But, because these are major chords, they belong in a different category. To make the distinction clear, let’s say power chords are the familiar two- or three-note shapes we see so frequently in hard rock.

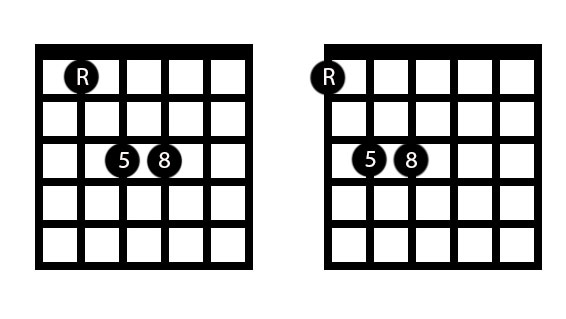

We’re going to call the two-note formation a perfect 5th, or just “fifth” for short. That means that if you take the lower sounding of the two notes and call it the first note of a major scale, the upper note will end up being note number 5 in the sequence. Sounded together, these two notes a 5th apart create our basic power chord. Adding the third note on the next string doubles the starting note an octave higher.

Making these distinctions between types of chords might be the most compelling reason for learning some basic music theory. Sounds can fall into categories based on their sonic quality. There’s math that corresponds, but that’s not the part musicians use in real time. If you think of music theory as a method to give names to different sounds, all we’re really doing is putting labels on your toolbox.

Keep in mind that these labels identify categories of sound, not just shapes!

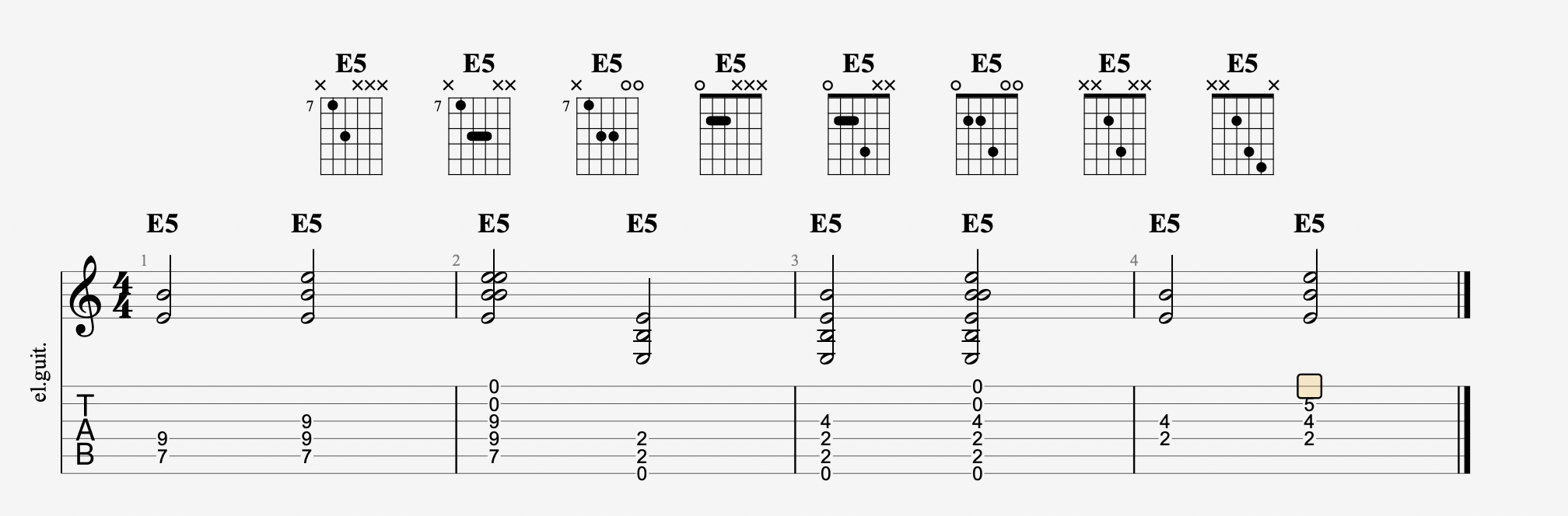

We already know we can play the same notes in multiple places. If we add more roots or fifths, it doesn’t change the chord’s name. The following chords could all be labeled E5, and notice how while the sound is obviously different the tonal quality or color is similar.

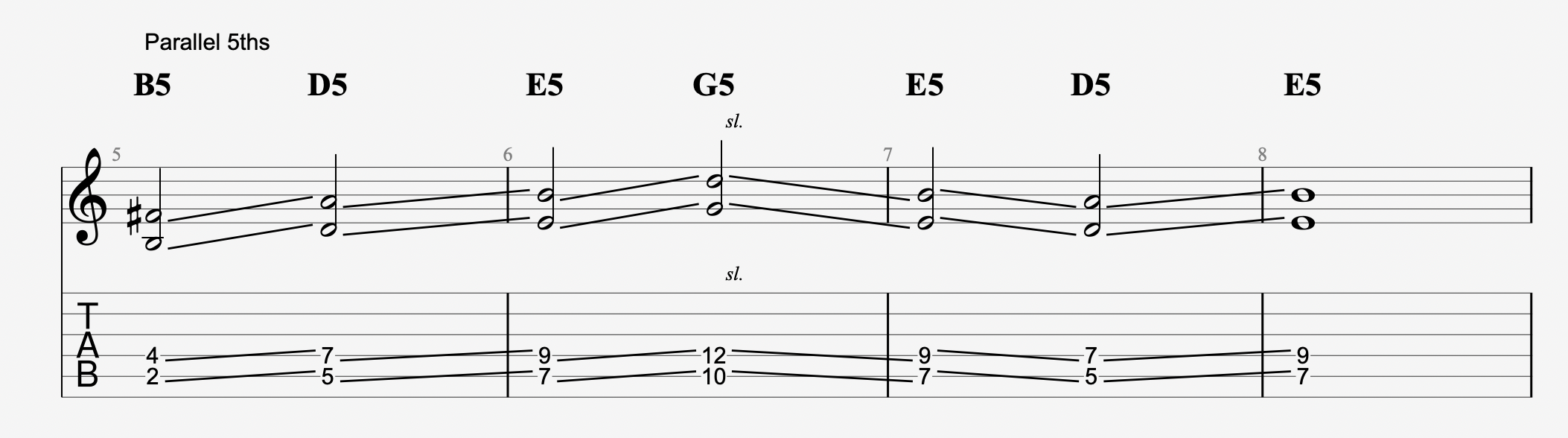

If you compare the sound of any of these to a familiar open E, the difference is obvious. Adding the major 3rd, G# changes the character of the sound to something richer and warmer. Returning to the E5, the sound is more open, with a natural bite and grind regardless of the shape. This is the sound we’re so familiar with, especially sliding that two-note form around:

If we reverse the two-note E5 and put the root note on top, we get a different, darker sort of grind. We’ve inverted our 5th and created a fourth.

Here’s where we have to be clear about something. Context is important in how we name things. Our understanding of a note is colored by the notes that surround it. So we can refer to the distance between two notes on the scale or the fretboard, and name the distance. In this case, four scale steps creates a fourth. BUT, in the context of the chord and key of E, the same two notes are still the root and the fifth if we name them individually.

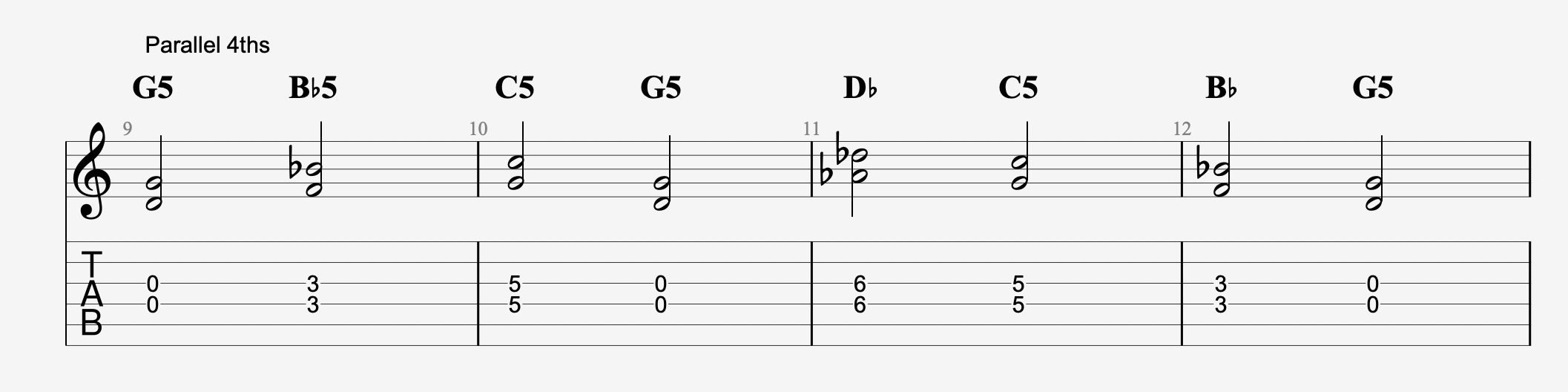

Got it? If not, don’t fear. You can see and hear the difference. Here is the same basic riff in fifths and then in fourths. Keep in mind the letter names are the same, and so is the name of the chord.

If your head hurts a little, it’s ok. Here are some classic examples of power chord riffs that use 5th or 4ths. Start listening for the difference and you’ll hear it.

If your head hurts a little, it’s ok. Here are some classic examples of power chord riffs that use 5th or 4ths. Start listening for the difference and you’ll hear it.

Black Sabbath, “Iron Man” – 5ths

Deep Purple, “Smoke On The Water” – 4ths

Judas Priest, “Living After Midnight” – 5ths

Rainbow, “Man On The Silver Mountain” – 4ths

This might be more than you ever thought you needed to know about the humble workingman’s power chord.

But, wait, there’s still more!

This example might be called “melodic power chords”. Sliding one finger down from the E root of our E5 creates a new interval and a new chord. In this case, our two-note interval gives us two of the three notes of a B major chord. Combined with 5ths, this new chord creates a smooth, melodic transition. This sound became popular in the late 70’s and early 80’s; check out Glen Tilbrook’s cool chunky rhythm playing in Squeeze hit “Nail In My Heart”, or the anthemic opening riff of .38 Special’s “Hold On Loosely”.

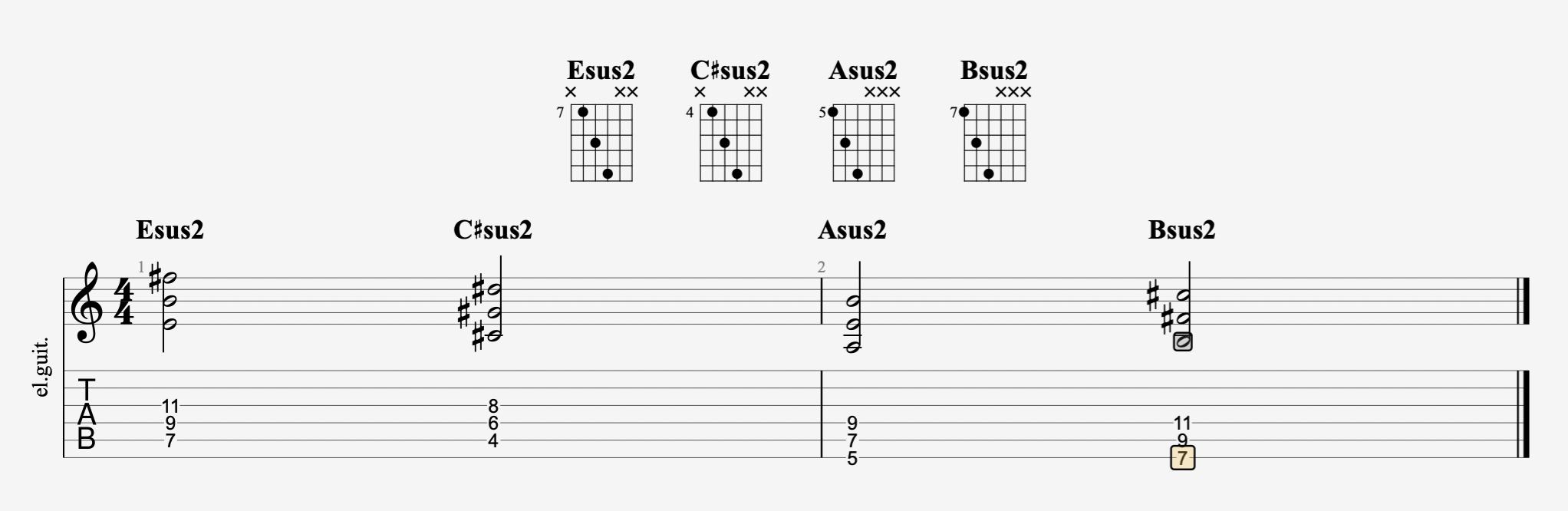

Still got room for one more? Double the root and raise it a step, creating an add9 chord. The most famous examples of this form come from The Police’s Andy Summers on songs like “Message In A Bottle” and “Every Breath You Take”, and it’s a cool substitute for a standard sliding form.

This kind of thinking can open the door to all sorts of new sounds: take a familiar shape and change one note. If you can connect the theory to categorize the sounds, great. If not, just listen for tone color, vibe, and atmosphere. This is what intuitive players do, and besides, the math makes a lot more sense when attached to a sound.

Interested in learning to solo on guitar? Check out JamPlay.com. JamPlay has over 450 guitar courses from 120+ instructors, and online guitar lessons tailored to every skill level, music genre, and playing style. Click here to learn more.

Dave Isaacs has established himself as a guitar teacher extraordinaire, having built a strong set of educational curriculums for beginner, intermediate, and advanced guitar players alike. Dave shares his expertise largely through video platforms, but also through his thoughtful writing. You can take guitar lessons from Dave Isaacs via his comprehensive video guitar courses on JamPlay.com.

Share this

Become a JamPlay member for unlimited access to 7000+ guitar lessons and 120+ artists and instructors. View membership plans ›