Another Way to Think About Guitar Modes

Guitarists spend a lot of time talking about modes.

Learning modes usually starts with a list of scale fingerings, and for a lot of people it never goes any further than that. For those that take the next step, there’s the math (theory) that determines which mode to use over a particular chord.

Those scale fingerings do have a purpose in introducing different sonic flavors. The theory gives you a way to categorize those flavors so you can use them intentionally. But learning those fingerings doesn’t get you there on its own. So what’s missing?

Every scale has a recognizable sound.

We could also say each has a particular flavor, color, feel – any other word that describes the way you perceive the difference between one scale and another.

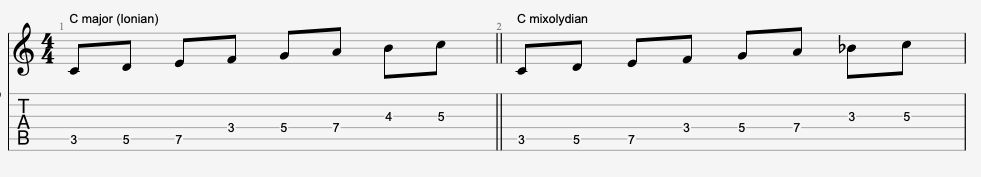

Here are two scales starting on C:

C major scale (Ionian): C D E F G A B C

C mixolydian: C D E F G A Bb C

Notice that the only difference between them is the seventh tone.

In the C major scale, the note is B, and we would call it the 7th of the scale. In mixolydian, we lower the seventh by a half-step. So we might say that the mixolydian mode has a flatted 7th or b7, in this case Bb.

Now play these two simple licks:

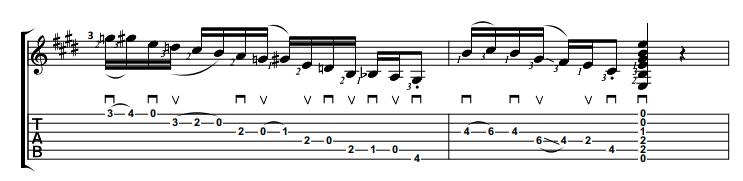

If we analyze the first lick, you might recognize a C major pentatonic. The second lick brings in the Bb, but also includes an Eb.

What’s going on here? Weren’t we starting with C major?

Was the major pentatonic a different choice of scale, or just a lick that happened not to include the seventh? And where did that Eb come from? That wasn’t in either scale either.

Every tone of the scale has a particular flavor you can learn to recognize. Odds are, for example, you can hear this in your head as you read. Maybe you can even sing it:

Do re mi fa sol la ti do

These are called solfège syllables and have been used for hundreds of years to help musicians communicate. In the European classical system, “do” always stands for C. That means that as young musicians learn, the syllables become connected to the pitches. This strengthens the players sense of what we might call absolute pitch: knowing that a C is a C just by hearing it. We generally call that “perfect pitch” and most see it as a gift some people are born with. But it’s absolutely something that can be learned. Many people describe different notes as different colors when explaining how they tell the difference.

Music students in the US learn solfège differently. American schools use a “moveable do” system, where “do” is the first tone of any major scale. This reinforces the student’s “relative pitch”, the ability to hear relationships between notes.

This is the skill that lets you differentiate between modes by sound alone.

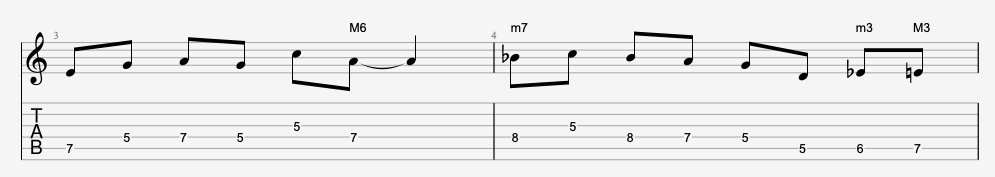

Every tone of the scale has a recognizable character. The difference between C major and C mixolydian is the difference between the sound of a major seventh or minor seventh. If you play a lick that pulls only some of the notes from C major but does not include the leading tone, we would still say we’re in C major. If you play another lick that includes a B-flat, you’ve arguably only altered one note of the scale rather than shifted gears into an entirely new one. Mathematically, the note actually comes from C natural minor. The relationship between major six and minor seven is a defining flavor of mixolydian. But it’s still just replacing one note with another: Bb instead of B.

The E flat in the second lick doesn’t belong to major or mixolydian, but it still works. The note is borrowed from C minor, an interval of a minor third up from the root. We’re using it as a stepping stone or passing tone to connect D and E. So the E flat doesn’t have to be accounted for in determining what scale you’re playing. We hear it as a set up for a note that does belong to the scale.

There are hundreds of variations of blues, rock, and boogie licks that use this expanded mixolydian sound. This lick incorporates the b7 as, mixed minor and major thirds, and the flatted 5th “blue note” before wrapping up with straight major pentatonic.

You can watch the Jamplay lesson here.

You can apply this kind of thinking to any scale, not just modes. Every tone has a flavor, and every tone has a note next to it that could be added or substituted to change that flavor.

This doesn’t mean you shouldn’t be learning those fingerings as well. But this way of thinking can start building the context that makes them useful. Here’s an introductory lesson on the mixolydian mode, from the “Learning To Lead” course.

Interested in learning to solo on guitar? Check out JamPlay.com. JamPlay has over 450 guitar courses from 120+ instructors, and online guitar lessons tailored to every skill level, music genre, and playing style. Click here to learn more.

Dave Isaacs has established himself as a guitar teacher extraordinaire, having built a strong set of educational curriculums for beginner, intermediate, and advanced guitar players alike. Dave shares his expertise largely through video platforms, but also through his thoughtful writing. You can take guitar lessons from Dave Isaacs via his comprehensive video guitar courses on JamPlay.com.

Share this

Become a JamPlay member for unlimited access to 7000+ guitar lessons and 120+ artists and instructors. View membership plans ›